The Keeper of The Temple

Eileen Bristol Honors the History of a Community by Keeping the Sahara Lounge Just the Way It Is

The front door of the club at night (Photo: Marina Petric)

IMPORTANT

* This story has not been adapted to cellphone screens yet *

AUSTIN, Texas – When Eileen Bristol and her two partners, Ibrahim Aminou and Topaz McGarrigle opened the Sahara Lounge in 2011 on Webberville Road in a historically African American part of Austin, they were carrying on a tradition of the neighborhood bar.

The Sahara Lounge was first known as the Lincoln Drive Inn in 1962 and then as RC’s, then TC’s before its current incarnation. To Bristol, the lounge is more than just one more live music venue in Austin.

“We keep the Sahara open because it’s our mission,” she says, with a smile, “Forgive me if this seems too ‘out there,’ but for me it’s like being the keeper of the temple. Of course, if I didn’t feel like this wasn’t good value for the community, I wouldn’t keep on doing it.”

Bristol has an eclectic career history, from working in her parents’ motorcycle shop, a biodynamic farm and as a massage therapist. A native of Houston, she has lived in Germany, Michigan, New York and North Carolina. At one time she was involved with the foundation of Austin Waldorf School and a program to bring meditation to people in prison. She studied philosophy at UT for “one-and-a-half semester,” until she realized she was looking for something else.

Music had always been a passion, but it wasn’t until she was in her 40s that she became a bass player. The Sahara is her first venture into running a music venue. Her so far longest running venture was the massage therapy business in Ann Arbor, which she directed for 11 years.

The Place

A bright lighted marquee with “Sahara” in funky red letters announces the bands of the night. String lights and light hoses draw lines around the tree next to the entrance and hang from the roof. The front of the house, with no windows, is fully covered by hand-painted murals celebrating African music and culture. A recent banner reads “BLACK LIVES MATTER.”

A hand-written sign announces the ticket price: $10 with African buffet.

Appearing to be part museum, the wooden bar is covered by a collection of African souvenirs like masks, fossils and old musical instruments. There are only a few bare square inches of wall in the entire venue. Posters remember special music nights, photos display its history, a big map shows northern Africa. There is a Brazilian flag somewhere, a Buddha under a lampshade, and an old photo of an Asian man. Two pool tables serve as a transition to the dancing floor and stage area.

At the door, Kalvin Foster exchanges wristbands for payment. Foster, 64, has lived in the neighborhood all his life and remembers going to the club when he was 16, and it was called T.C.’s.

“This place still reminds me a lot of the old T.C.’s. This part wasn’t here,” he points to the area of the stage, “and the patio outside wasn’t part of it, but all the rest feels the same. It’s the same vibe.”

Post from RICOH THETA. #theta360 - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

3D photo shows the Sahara All Stars playing to a limited capacity (Photo: Marina Petric)

Origins

Bristol developed the idea for the Sahara with her partner Ibrahim Aminou long before moving back to Austin. Aminou was born in the village of Dineye, in the Republic of Niger. Music, and particularly African music, has always been a part of his life.

“The idea of the club came from a dream that Ibrahim had in Ann Arbor,” Bristol said. “He told me that in his dream he and I had a club in Austin.”

Bristol, already a bass player at the time, embraced her partner’s vision and made it the couple’s project. Focused and passionate, she and her son Topaz McGarrigle, who was already living in Austin, researched the market.

After a few visits and conversations, she acquired T.C.’s, a music venue that had been operating in East Austin for for 33 years. She remembered frequenting blues nights at T.C.’s Lounge years ago when she lived in Austin.

It was Bristol’s first venture into bar ownership.

“People said to me, ‘You know what are you doing, Eileen? You know how old you are? You never even worked in a bar,” she remembers, laughing, “and I am like ‘ah, it will work out.”

And it did, but it was tough at first.

“The beginning was horrible,” Bristol remembers, “I borrowed so much money. But anyway, we were stubborn about it and we kept going.” She recalls that at one point she said to Aminou that she didn’t know if they were going to survive as a business. That’s when he suggested a “Ladies’ Night.”

She recalls asking “What is a Ladies’ Night?” to what Aminou responded “you have, like, 80s music, it’s free for women, the guys pay $5 dollars.” Bristol then made a Facebook post and saw people ‘liking’ it immediately. “That was our big money maker,” she said.

History

One of the things that appealed to Bristol was the history of the building and the neighborhood.

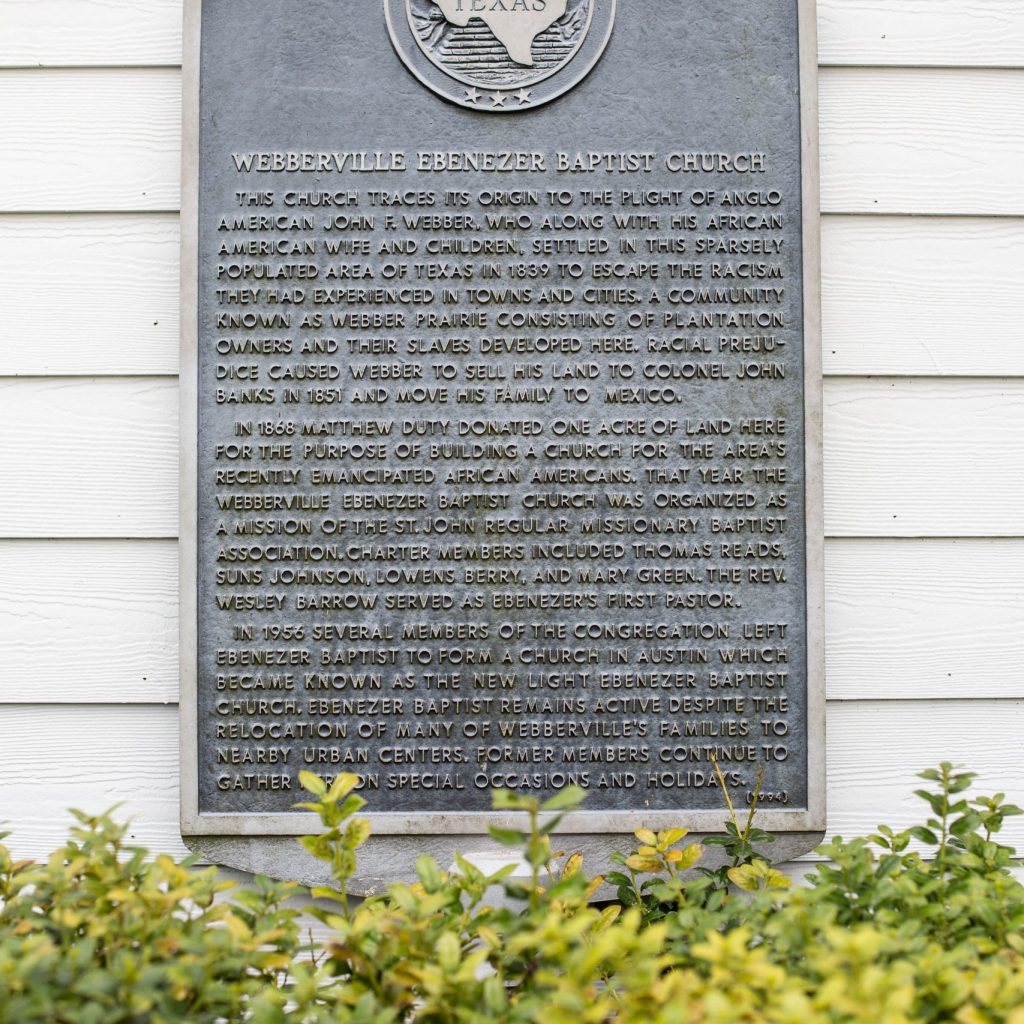

The club is located at 1413 Webberville Road. The road has been part of a large Black community that dates to the 1800s. Webberville, the town adjacent to Austin and where the road leads, is named after John Webber, who along with his African American wife settled in a sparsely populated area of Texas in 1839 to escape racism – according to a historical marker on Webberville Ebenezer Baptist church. By then, the area was based on a cotton farming economy.

Community

Bristol is more than the bar owner, she also plays bass with a few of the bands at the club, including her partner Aminou’s band, Zoumontchi, Abou & the Crew and the Sahara Allstars.

Austin-based band Atash has been playing at the Sahara for several years. Atash’s music is what is usually labeled “world music,” that is, something that doesn’t include words in English and introduces a variety of rhythms, instruments and players from other countries. Atash combines an Indian sitar, a flamenco guitar, two classical violins, African drums, acoustic bass, an oud and Persian poetry – a melting pot that fits the atmosphere of the Sahara just right.

On Friday nights before the pandemic Atash frequently played after after a few Brazilian bands, such as Seu Jacinto, Macaxeira Funk, Tio Chico and Bamako Airlines. During these international nights, the club is a unique representation of diversity – the usual racial and age variety adds to the mélange of languages that can be heard in the patio outside. It is not unusual to hear Portuguese and Spanish.

To Roberto Riggio, Atash’s musical director and violinist, the Sahara is one of the few spots in the city where the old laid-back, diverse and open spirit of Austin is preserved.

“It’s got the sort of quirkiness of old Austin culture, and the feeling of acceptance – like, ‘anything goes!’ – of the Austin culture that attracted me here in the first place,” Riggio said. “The characters who inhabit the neighborhood are very much a part of the culture of the venue.”

Riggio said he treasures the venue.

“Because it’s in such a removed neighborhood, it only commands the kind of crowd that seeks it out, people who are in the know,’’ Riggio said. “I’m more apt to hang out with people at Sahara than anywhere else in town, just because the atmosphere is so inviting.”

Challenges

The coronavirus pandemic has forced the club to temporarily close multiple times, either because of city lockdowns or because of its responsibility regarding the spread of the virus. The first time it closed was in mid-March, days after SXSW was canceled. It reopened in June after the city approved the opening of bars, but that didn’t last long. Sahara reopened at the end of October for about two months, and closed again in December, when Austin reached stage 5 COVID alert. During the year, a few bands live-streamed from an empty Sahara.

The club finally reopened and remained open in January.

Bristol and other advocates motivated the city’s government to take action. She received a grant from the city, and the Payment Protection loan (PPP) helped her keep the doors open for her staff to come back to work (although some preferred to stay home on unemployment). She hired a few new employees. The Economic Injury Disaster loan helped her get through the months when the club wasn’t open. By renovating the kitchen and applying for a new Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission (TABC) license, she opened the doors again in November serving food.

“In November we received a city loan that was of tremendous help, and now I know they’re looking into managing property taxes in places where venues are,” Bristol said.

Bristol is protective of the club as the neighborhood succumbs to gentrification.

“One day a guy came in and introduced himself,” she remembers. “He was from California and he bought some property around the corner. He is building two houses. One of the houses is going to be his vacation house, and the other one he’s going to rent out. He wanted to know if I was selling this land. I was shocked. I was like, ‘how can anybody think that we would want to tear down our club so you can build some condominiums?’ And to him it was obvious.”

Bristol plans to keep the club going far into the future. Ladies Night returned in May and she is hoping to see Atash return by fall. Africa Night, featuring house band Zoumountchi, continues to serve the community every Saturday.

May 31 2021