Brazil: What Happens on YouTube, Doesn’t Stay on YouTube

Main Takeaways:

• YouTube became a powerful tool for anti-Bolsonaro communicators in Brazil.

• Brazilian journalism needs to adapt to this new form of para-personal / inter-personal interaction now, rather than later.

• YouTube “tribes” are a strong tendency in Brazil.

Note: The concepts of “left” and “right” in the United States can be applied only in the U.S. context. Every country’s “left” and “right” have other meanings that are unique to those countries. Therefore these terms are avoided in the text, but not in the interviews with Brazilians.

Last February 11 Bruno Aiub, better known as “Monark,” said in his popular YouTube show that the Nazi party should have the right to exist in Brazil, where it is outlawed.

Monark’s problems started immediately and culminated with him leaving the program, YouTube banning him from creating another channel, and the police opening an investigation of him.

The case generated another round of debates about freedom of expression, including long threads on twitter. But mostly it entered the “traditional media” agenda, both in Brazil and internationally (The New York Times, BBC, The Jewish Telegraphic Agency).

This was not the first time that Brazilian YouTubers caused an uproar. In 2021 the YouTuber Luccas Neto became a headache for parents in Portugal who didn’t approve of their children learning and speaking Brazilian Portuguese. This year, as his young audience continued to increase in Portugal, it has been agreed that Neto’s videos will be dubbed to European Portuguese.

These two cases show how the “alternative” media, which used to follow the mainstream media agenda, is now able to invert the direction of this dynamic.

These two cases show how the “alternative” media, which used to follow the mainstream media agenda is now able to invert the direction of this dynamic.

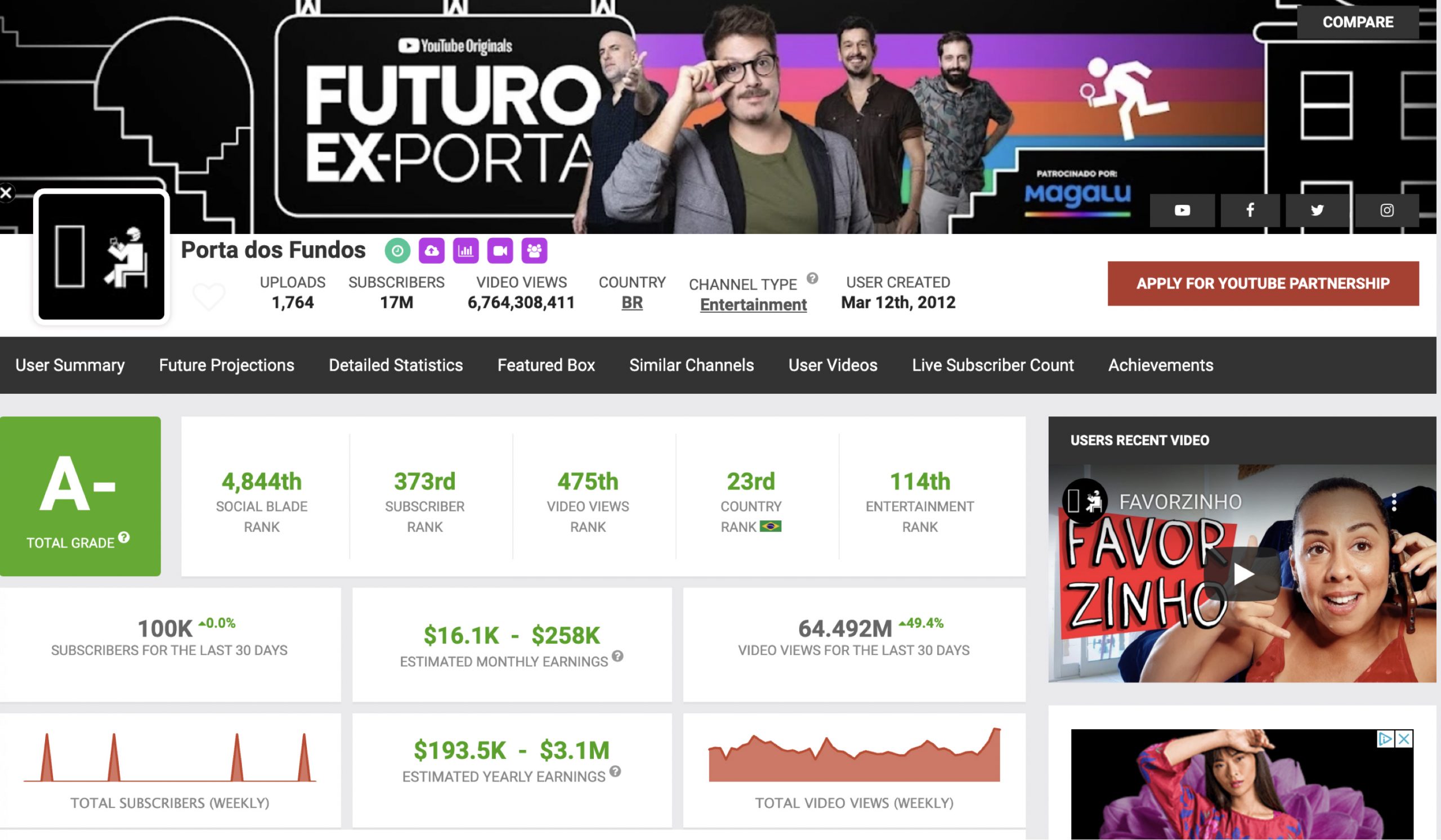

Porta dos Fundos [Backdoor], is a YouTube channel created in 2012. Among many achievements, and in less than a year of existence, Porta dos Fundos became the first Brazilian channel on the internet to reach the milestone of 1 million subscribers.

In reaction to this “Brazilian disinformation machine” an informal network of users on YouTube established a fight against disinformation and dissemination of false content.

Brazil has a successful history with alternative media.

During the military autocratic regime (1964-85), O Pasquim left its mark in history. O Pasquim was a weekly periodical, established in Rio de Janeiro in 1969 that soon became a national phenomenon. O Pasquim used humor to critique political coercion and the systematic violation of human rights by the Brazilian dictatorship.

Porta dos Fundos [Backdoor] is a YouTube channel created in 2012. Among its many achievements, within a year of its founding Porta dos Fundos became the first Brazilian channel on the internet to reach the million-subscriber milestone and won the prize of PAAC (Paulista Association of Art Critics) for Best TV Comedy. By 2014, the channel was the 16th-most subscribed channel on YouTube.

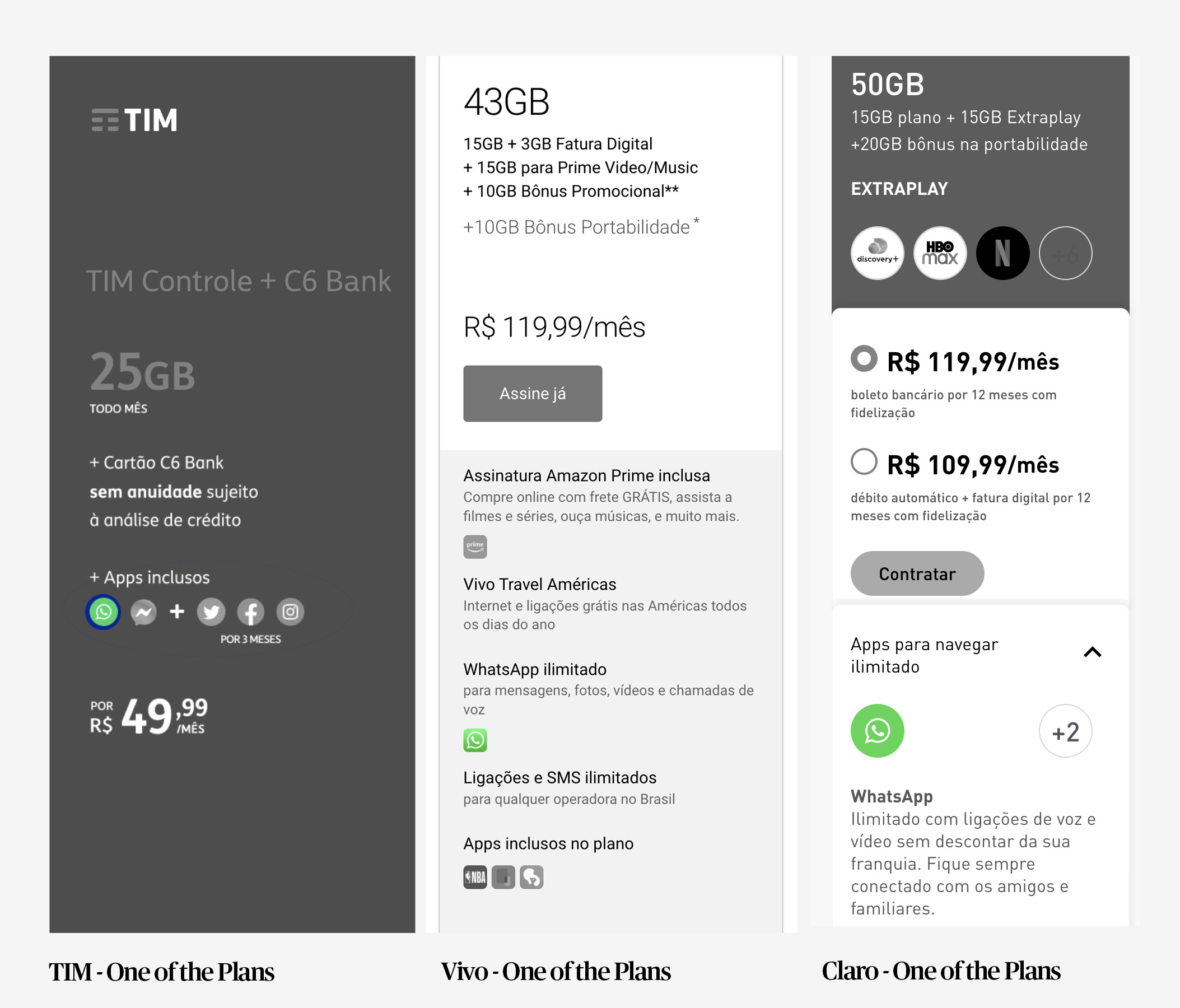

During the 2018 presidential elections in Brazil, YouTube and WhatsApp walked hand-in-hand. As most Brazilians access the internet via cellphone and most are restricted to a limited data plan, WhatsApp worked as a pipeline for Bolsonaro supporters and allies, who used short YouTube clips to disseminate political disinformation while introducing new channels.

The New York Times covered this relationship in this article, which also shoes how algorithms might have played a decisive role in Bolsonaro’s rise. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm boosted extreme videos into the mainstream and helped spread misinformation.

During the 2018 presidential elections in Brazil, YouTube and WhatsApp walked hand-in-hand. As most Brazilians access the internet via cellphone and most are restricted to a limited data plan, WhatsApp worked as a pipeline, using short YouTube clips to disseminate disinformation while introducing new channels. The New York Times covered this relationship in this article, which also shoes how algorithms may have played a decisive role in Bolsonaro’s rise. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm boosted extreme videos into the mainstream and helped spread misinformation.

Data Packages and YouTube

The key to understanding much of what happens in Brazil is the cellphone data packages. In these limited-data access plans, some apps are offered with unlimited access. The apps vary from company to company, but WhatsApp is in all of them. This is one of the causes and consequences of Brazilians doing so much via WhatsApp, which is installed in 99% of Brazilian phones.

Fact-checking websites and groups created to fight disinformation, such as Agencia Lupa and Sleeping Giants, popped up after 2018. Brazilians seem to be more aware of the existence of “fake news,” but some need access to data that sometimes is outside their data plan: If it is outside of WhatsApp, it may be out of reach.

Some companies, however, in the past year started including Instagram and Facebook in the data packages. This allows YouTubers to post their videos in these platforms as well.

Even though the way WhatsApp groups work has changed since 2018, the app still permeates the country. In 2018 the journalist Patrica Campos Mello denounced the “chipeiras” – hubs filled with phone chips that bombarded main influencers in the chain, which in turn, spread the information to the base of the misinformation pyramid – the majority of the population. Today WhatsApp shares this (disinformation) role with Telegram, which in its turn sends users to video content on YouTube. A lot of this dynamic can be explained by how much is invested and how much is needed to return to the campaign creators. YouTube pays better than other platforms.

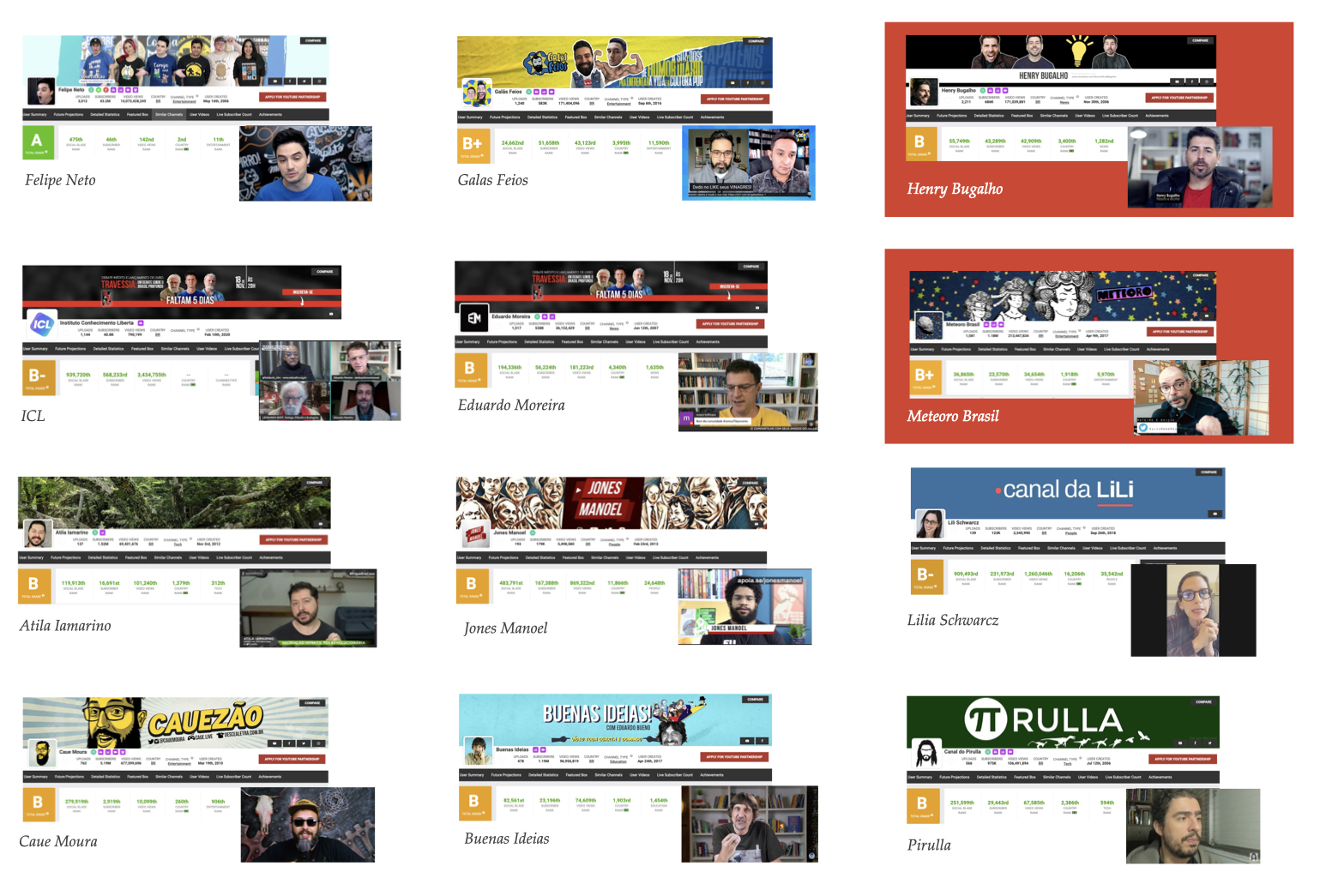

In reaction to this “Brazilian disinformation machine” an informal network of users on YouTube established a fight against disinformation and dissemination of false content. These channels are part of a mobilization and resistance campaign on YouTube. Together, they shaped a growing movement that aims to share ideas to raise the debate and give depth to dialogue and common sense.

Some of these channels became very popular in 2021, as the need for information about the pandemic became urgent and trust in the government plummeted. More Brazilians turned to entrepreneurial media as the country kept falling into the today’s economic, social and political disarray.

Some of these channels became very popular in 2021, as the need for information about the COVID-19 pandemic became urgent and trust in the government plummeted. More Brazilians turned to entrepreneurial media as the country began falling into its current level of economic, social and political disarray.

Two interesting cases of dissent YouTube channels are Meteoro Brasil and Henry Bugalho.

Overview of the Legacy Media Scenario

Legacy media are dominated by the Globo Network (Rede Globo, or simply Globo), one of the largest media companies in the world and the top-rated network in Brazil. Considering its daily programming, Globo’s average number of viewers was 9.37 million throughout Brazil’s 15 largest media markets in 2019, more than the next two largest networks combined (Statista).

Electoral media campaigns should be seen within the context of beliefs, expectations, discussions, ceremonies, rituals, symbolism, gestures, memories, and myths that define a society. As an example, consider the case of Collor de Mello’s election.

TV Globo was the principal instrument that Collor’s supporters used to construct the political scenario that made his election possible. TV Globo’s popular “novelas” (short for “telenovelas,” TV serial dramas produced primarily in South America) were an important component in the construction of the political scenario, setting the stage for the 1989 presidential election.

In 1989, Brazil held its first democratic elections in 29 years, after a period of military dictatorship. In the second and final round, two candidates were running for the presidency of the new democratic republic: Lula da Silva and Fernando Collor. Two days before the election, Rede Globo, by far the most popular broadcasting television network in Brazil, broadcast a montage of the final debate between the two candidates during its prime-time news program, which reached 61 rating points.

In 1993 this event was discussed on Channel 4‘s documentary “Beyond Citizen Kane.” The director Simon Hartog argues that, while Rede Globo is a private company, it needs a public license to operate, so its journalists manipulated the montage in favor of Collor.

Globo’s 2021 vignette. The “plim-plim” sound has never changed.

From the beginning, Roberto Marinho, the owner of the Globo network, supported Collor as the only candidate capable of keeping the forces of the left and center-left out of power. Over time, an increasing number of conservative politicians and businesspeople joined the bandwagon.

Just as Globo had leveraged the Collor election, it also played a decisive role in his impeachment two years into his presidency. For the impeachment, Globo produced another novela that portrayed politically engaged university students. The story took place in the late 1950’s in Brazil and was called “Anos Rebeldes” (Rebel Years). The protagonists organized public demonstrations against the dictatorship and painted their faces yellow and green (the colors of the Brazilian flag). It did not take long for the population to take to the streets in painted faces (the “caras-pintadas,” or “painted-faces”) to demand Collor’s impeachment. In one of the first pro-impeachment marches, a demonstrator carried a poster that read “Rebel Years, Next Chapter.”

Today Globo’s main audience-grabber is Big Brother Brazil, or simply BBB. Globo is still a giant, but it may slowly be showing signs of weakness.

June has always been a weak month for viewership throughout Globo’s history. In June 2021, however, Globo had some of its worst-ever audience levels. This loss was attributed to the migration of viewers to streaming channels and the Internet in general.

Visual Identity

Even the untrained eye can recognize corporate-like visual elements. Graphic design – visual framing in general – is vital to the positioning of a brand. The Nazi party never underestimated the power of posters, colors, lighting, body language or architecture. The Nazis had a particular aesthetic, which was carefully manipulated by Goebbels and Hitler himself.

Today, particularly after Steve Job’s legacy with Apple, corporate designs are clean, simple and heavily reliant on photography.

Globo’s visual language is far from Steve Job’s style; however, it is imprinted in every Brazilian brain with its unique sounds and heavy use of computer generated 3-D images, a mark left by the Brazilian-Austrian designer Hans Donner.

“In the beginning, they didn’t show their faces,” says Agatha Rodrigues, 35, a professor of statistics at the Federal University of Espirito Santo. “They used to wear a mask or let the animations do the talking. They didn’t want to be identified. This was around 2018, 2019. But I already loved them because you can identify charisma by the voice, right?”

On Rodrigues’s “Analyzing YouTube’s Best Channel” webpage, the professor demonstrates a step-by-step process showing how to use code to capture the channel’s statistics. Her knowledge of the history of the channel and her admiration for Meteoro frame the tutorial.

“I like other channels, too, but what I mostly appreciate about Meteoro is that their videos make me stop what I am doing and give them my complete attention. The videos are 15, 20-minute long, sometimes even longer, and they all display a great amount of research. I think they must have a research team. The channel is going to grow,” she adds.

Meteoro Brasil (or simply “Meteoro”) is the brain-child of the couple Ana Lesnovski and Alvaro Borba, 38. Lesnovski has a Ph.D. in mass communication from the Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul. She has written about the intersection of narratives and interactivity in its electronic and audiovisual forms. Borba graduated with a degree in journalism from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, worked in radio and TV, was chief editor at TV Bandeirantes and later as chief reporter at Radio CBN. On its official website, Meteoro Brasil defines itself as a website about pop culture, science and philosophy.

Meteoro’s visuals immediately catch the audience’s eye. A cutout of a meteor photo and hand-drawn elements fluctuate over a background that looks like fabrics, with little stars in many colors. The word “Meteoro” is also hand-written against a lilac-pink background. The videos end with Ana Lesnovski levitating and saying the final “thanks” as an astronaut. The animations are flat, which adds to the home-made feeling. The light-hearted opening song completes the atmosphere.

For Rodrigues, Meteoro’s visual elements initially were so raw simply because of limited resources, but along the way they made an impression and became the channel’s brand. Marketers and branding experts may have another opinion.

In every sense, Meteoro’s brand is the opposite of what Brazilians became used to seeing on Rede Globo, the broadcasting giant.

On channels like Meteoro, the audience is actively voicing opinions and feelings in live and asynchronous chats. The atmosphere is that of a big living room with viewers and hosts: Their dog walks by, the couple kiss goodbye as one leaves, and some personal stories are shared.

If the channel produces a video based on a researcher’s work, the researcher is asked to voice the narration. This fact is not to be underestimated, for it allows a multitude of Brazilian accents and idiomatic expressions – setting these channels apart from big networks like Globo, where the “standard Portuguese” is from Rio de Janeiro or Sao Paulo.

In Meteoro, the trend of escaping the sanitized corporate world and its computer-generated surfaces meets the “we are just like you” feeling. The perception of amateurish and even childish visuals at first glance hides a brand that caught the pulse of a certain public. It is not amateurish at all: that raw feeling that Rodrigues attributed to limited resources completely aligns with the channel’s philosophy. The homemade video look is a success.

Lesnovski and Borba acquired a new space in December 2021, paused the video production for a month, and restarted with better camera and sound. Now the white balance is fixed, the light and the sound are better, the backgrounds are more elaborated and the angles are more appealing – but otherwise, nothing changed. The intimate feeling is there, the border collie Eva roams around, and the couple continues talking to the audience and to each other as before.

Language

“For me, what is more important in Meteoro is their non-violent use of language,” says an 45-year old woman scientist in Rio.

Victor Klemperer, a journalist and professor who lived through the Nazi state to the German Democratic Republic, wrote in his book The Language of the Third Reich, “It isn’t only Nazi actions that have to vanish, but also the Nazi cast of mind, the Nazi way of thinking, and its breeding ground: the language of Nazism.”

The number of Brazilian neo-Nazi groups has soared by 270 percent in the past three years. Anthropologist Adriana Dias has been collecting and printing whole neo-Nazi websites (before they are deleted) and denouncing neo-Nazi groups on the Internet since 2002. She talked to The Intercept’s Leandro Demori about this phenomenon and showed proof of these groups have been supporting Bolsonaro since 2004. In one of the documents, the now-president says, “You are the reason I am in this position [a congressman].”

The existence of this Neo-Nazi shadow in Brazil today is key to understand how Meteoro’s non-violent use of language is so well-received.

“I like that they give space to all people at the end of some videos,” says Rodrigues, the statistics professor. “For example, last week a couple wanted to honor their son. Meteoro read their short text at the end of a video; this happens a lot. I like that they give that kind of mindful space to their supporters.”

The scientist and Rodrigues agree that the lack of verbs in the imperative is another characteristic of the channel. “All channels ask for donations, right? Like ‘support us,’ ‘donate now,’ and so on. But they always say, ‘You can donate, but only if you want.’ I like that. They are innovative in that way, too,” says Rodrigues.

A music teacher from a small city in the state of Rio has another opinion about that language. He watches the channel but confesses, “They are too nice for me. I am not that nice.” Therefore, he turns to Galas Feios (Ugly Gallants), a channel created by Helder Maldonado and Marco Bezzi, two journalists from Sao Paulo who share a sarcastic view of the Bolsonaro government and provide a much-needed cathartic laugh for the audience.

A psychologist and professor at a university in a city near Rio de Janeiro, who does not want her name spelled out in text for political reasons, says she trusted Meteoro for the daily CPI updates. The CPI (Comissao Parlamentar de Inquerito, or Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry), began in April and went through November 2021. The commission’s goal was to investigate alleged omissions and irregularities in federal government spending during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil.

The CPI hearings were live-streamed by Meteoro and many other channels, but Meteoro acquired the greatest number of new subscribers during this period. On September 29, 2021 more than 34,000 people watched the CPI on Meteoro Brasil’s channel. The channel’s chat rolled so fast that it was impossible to read every comment. Meteoro’s “living room” became a party and a guided view of the process.

The music teacher explains why he turned to Meteoro to listen to the CPI sessions: “It was impossible to stomach all that without a mediator. It was impossible to listen to [Congressman Luis Carlos] Heinze. Every time he spoke, people asked the channel to play a nice song instead, and so they did.”

Meteoro Brasil: Good Laugh CPI Live Transmission – Aug 10, 2021

Link to the 12-hour video

Meteoro produces several categories of videos: interviews, documentaries, science, data, biography, TV, shorts and animations. When a contributor shares his or her work, Meteoro gives them the narration too. This provides the audience with a rich variation of national accents, giving the channel opportunities to be as inclusive as possible.

The model of a quasi-intimate conversation shared directly from the home (now studio) of the hosts succeeded with the audience. Visual framing supports the content, emphasizing the conversational tone and rejecting the established corporate aesthetic. Meteoro’s visual framing produces an aesthetic that evokes stronger responses from viewers. It is not passive, but rather a fundamental part of the message.

Meteoro Brasil was contacted for a brief interview in October 2021, but declined the invitations with a very polite (and maybe loving?) email.

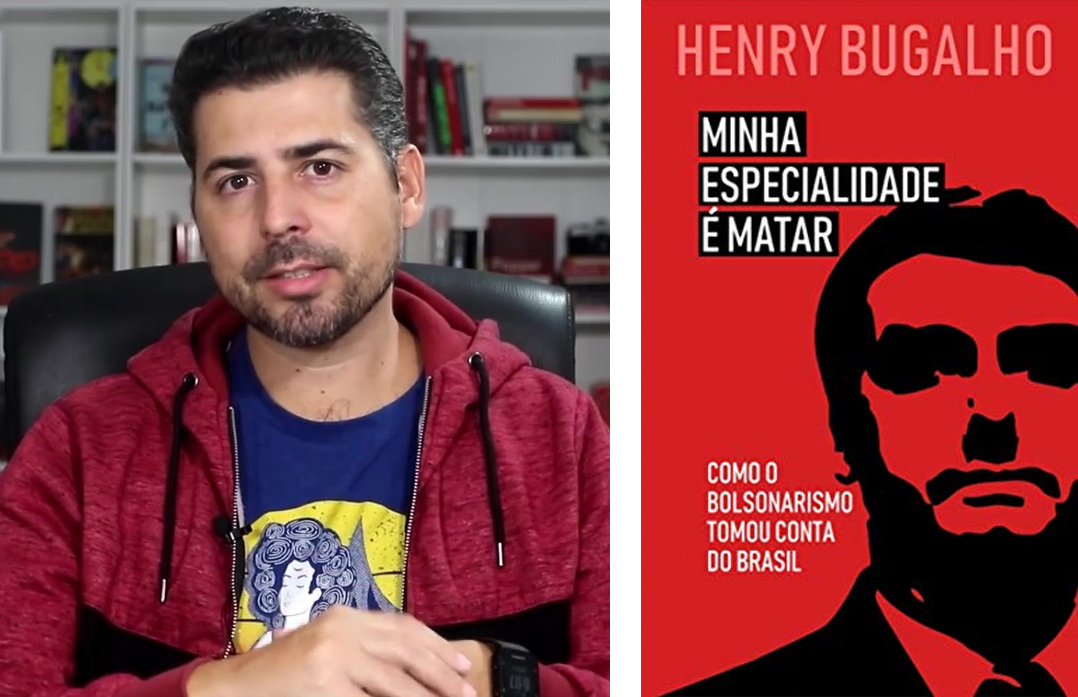

Henry Bugalho, 42, is a Brazilian philosopher from Curitiba, writer, and translator. His YouTube channel was originally created in 2006 to discuss literature, art, and philosophy, but in recent years his focus has turned to politics.

2006 was also the year that he and his family (wife and child) left Brazil to lead a nomadic life. They lived in Argentina, Italy, England, the United States, Portugal, and now in Alicante, Spain. Throughout these years, Bugalho maintained a YouTube channel and wrote novels and non-fiction, such as a series about his experiences as an immigrant in the countries where he lived.

In 2018 Bugalho publicly expressed his opposition to the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and essayist Olavo de Carvalho, a self-entitled philosopher and extremist, who was revered as a guru by Bolsonaro and his supporters.

Among his published works is My Specialty is Killing (Minha Especialidade e Matar), a book about Bolsonaro.

On his YouTube channel, Bugalho is an academic with a passion for talking with those outside the ivory tower. He is an excellent communicator, a philosopher dedicated to analyzing quotidian ideas, as small as they may seem. For him, philosophy is an action and a tool to be applied to analyze ideologies. He does not lecture about philosophy – rather, he looks at the world, especially Brazil, through the lends of a philosopher. He covers Fascism, Marxism, Fascism and other movements in depth, but with great clarity, in a palatable way for non-philosophers. His themes vary, but some consistent topics are Nazism and its origins, rhetoric, logic fallacies and cognitive biases.

Recently, Bugalho was involved in the debate about freedom of speech prompted by Monark’s case. The journalist Glen Greenwald exchanged tweets with him, defending complete freedom of speech, while Bugalho supported the unlawful existence of a Nazi party in Brazil.

The last paragraph may sound bewildering to Americans, who know the shield of the first amendment. In Brazil, however, the existence of an official neo-Nazi party is not protected by law.

The video below shows Bugalho explaining why he is talking about a “minor” event. Note the photography.

Bugalho’s channel is austere, with rare use of graphics. He makes good use of the camera: The angle is right, the depth of field is good, the white balance is constant (rare in many other dissent channels). One can tell how he learned to use YouTube’s algorithms better over his years on the platform: His titles are eye-catching; his themes are always timely and relevant; the few colors he uses are basic but consistent.

The scientist in Rio, from , says she is not attracted to Bugalho’s channel. One of the reasons, she says, is the visual aspect: “It’s only him and the camera. I prefer to watch Meteoro. They have all those animations and images, it’s more dynamic.”

Meteoro and Bugalho’s channels cannot be strictly compared, but their viewership partly overlaps — as with the psychologist, who considers both “excellent.”

Bugalho publishes one video a day during weekdays (that is one of the reasons he can talk about current events) and also posts videos on weekends. He has made it clear that he values a healthy work-life balance, after suffering a heart attack in 2020.

Other Graphics from Google Trends

Notice the peak in searches for “Nazism” on 6/13/2021.

As Henry Bugalho covers this theme repeatedly, his channel also had a peak in audience that day.

Don’t put all eggs in one basket. This is Leandro Demori’s approach to the question of financing. Demori is the executive editor of Intercept Brasil, based in Rio de Janeiro.

In the weekly YouTube series Cama de Gato (Cat’s Craddle), Demori talks to the audience live, bringing up relevant information from the week and answering questions submitted via “super chats” (super chats and “super stickers” are tools to monetize the channel – viewers pay a certain amount to have their question pinned to the video or answered). The debate is lively and feels personal. Demori is good at answering questions using people’s names, and his language is informal and precise.

Demori says that his audience on YouTube is comprised of people who do not read Intercept Brasil and who have not heard about his books. He is surprised by the number of times he hears “I didn’t know about The Intercept,” so Cama de Gato also serves as a gateway to the newspaper readership.

He is currently contemplating the idea of having Cama de Gato members, which would monetize an “extended chat” for subscribers only.

Monetization of videos on YouTube must follow the platform rules and be subject to Google’s decisions. In an ideal world, for Demori, his videos would remain independent from third parties. However, there is no doubt that YouTube today offers endless possibilities to reach new publics while maintaining current readers.

To maintain its independent status, The Intercept Brasil depends on donations. The business model does not accept large donations from companies, and Demori says in the video, “It’s better to have a million donors chipping in one Real (Brazilian currency) than having one donor sending us a million Reais.”

Monetization of videos on YouTube follows the platform rules and is susceptible to Google’s decisions. In an ideal world, for Demori, his videos would remain independent from third parties. However, there is no doubt that YouTube today offers endless possibilities to reach new public and maintain current readers.

The pandemic has trained Brazilians to improve video ratings by adding a “like.” Channels without YouTube monetization, such Eduardo Moreira’s channel, have survived thanks to “likes” and shares on social media.

People want to be heard and seen, to be part of the debate and to make a difference. Talking directly to the journalist, in this case Demori, adds a personal layer to information so that trust is created or deepened.

This parapersonal relationship with the public seems to be the key to opening new doors for journalism in Brazil.