The Case of Germany

NetzDG

Impact and Evolution

From abroad, the law was received with joy by governments who limit free speech and force companies to act as their censors. Some examples include:

- In Singapore, a country with a record of using overly broad criminal laws to chill free speech, the government is citing the German law as a positive example as it proposes ways to tackle “fake news.”

- In the Philippines, the Act Penalizing the Malicious Distribution of False News and Other Related Violations was submitted to congress in June, referencing the German law. The bill proposes fines for social media companies that fail to remove false news or information “within a reasonable period” and imprisonment for responsible individuals. It is currently with the Committee on Public Information and Media and is one of the measures being discussed in a Senate hearing on ways to tackle fake news.

- In Russia, the ruling United Russia party submitted two draft laws to the State Duma in July to regulate online content. Citing the German law, one of them requires social media platforms with more than 2 million registered users and other “organizers of information dissemination” in Russia to remove, within 24 hours of receiving a complaint, certain types of illegal content, such as information that propagates war; incites national, racial, or religious hatred; defames the honor, dignity, or reputation of another person; or is disseminated in violation of administrative or criminal law. The other law levels fines for failure to remove illegal content (from 3 to 5 million rubles (US$53,220 to $88,700) for individuals and from 30 to 50 million rubles (US$532,200 to $887,000) for legal entities. The first law has entered the first hearing stage and the second law is still under review.

- In Venezuela, the pro-government Constituent Assembly on November 8 adopted the “Anti-Hate Law for Peaceful Coexistence and Tolerance.” Among other provisions that restrict free speech and association, the law imposes high fines on social media platforms that fail to delete content that “constitute[s] propaganda advocating war or national, racial, religious, political, or any other kind of hatred” within six hours of posting.

- In Kenya, the Communications Authority issued guidelines in July that oblige social media platforms to close accounts that have been used to disseminate “undesirable political contents” within 24 hours after it is brought to the platform’s attention, though no one is known to have been punished yet. Undesirable content includes political messages that are “offensive, abusive, insulting, misleading, confusing, obscene or profane language.”

- In Europe, the European Commission has called for social media platforms to assume greater responsibility for identifying and removing illegal online content, including a code of conduct for IT companies. The UK and French governments have been developing a joint action plan to improve the identification and deletion of online material that state authorities find terrorist, radical, or hateful. Their proposals include pressing companies to automate the detection and speed up the suspension or removal of illegal content, as well as provide access to encrypted content.

- In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Theresa May recently called on large social media companies to do more to identify and remove terrorist content. One of her ministers called for tax penalties against tech companies that were slow to remove content or refused to give the government access to encrypted messages

Overall Results and Current State

In its first year, the law seemed to be neither particularly effective at solving what it set out to do, nor as restrictive as many feared. However, without more insight into the kinds of notices that are being sent and the methods and guidelines platforms have adopted to handle them, it’s difficult to assess the real impact.

The law was praised by some politicians as an important measure to curb hate speech and vehemently opposed by others. It was widely criticized by digital rights groups concerned about threats to free speech and overbroad takedowns.

Studies show that the reality is in between these extremes. NetzDG has not provoked mass requests for takedowns. Nor has it forced internet platforms to adopt a ‘take down, ask later’ approach. At the same time, it remains uncertain whether NetzDG has achieved significant results in reaching its stated goal of preventing hate speech.

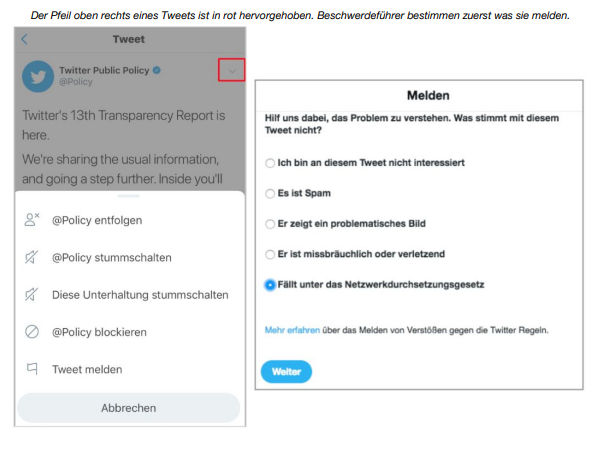

“If we want to better understand how companies make decisions about acceptable and unacceptable speech online, we need a more granular understanding of case-by-case determinations,” wrote researchers from Germany’s Alexander von Humboldt Institut für Internet und Gesellschaft in reaction to the reports. They call for greater transparency and insight in order to understand what the effect of the law has been: “Who are the requesters for takedowns, and how strategic are their uses of reporting systems? How do flagging mechanisms affect user behavior?”

While most platform content rules are understood to be based on terms of service, community guidelines and other user policies, relatively little is communicated directly by platforms about how they enforce their own rules on prohibited content.

In Germany, an opportunity to come out of a contentious and politicized debate about harmful content with greater knowledge and better solutions has so far not materialized. Greater transparency around the sources of hateful and violent speech online, who reports it and how takedowns are approached by intermediaries would be an important step toward understanding how to foster a healthier internet for all.

2020

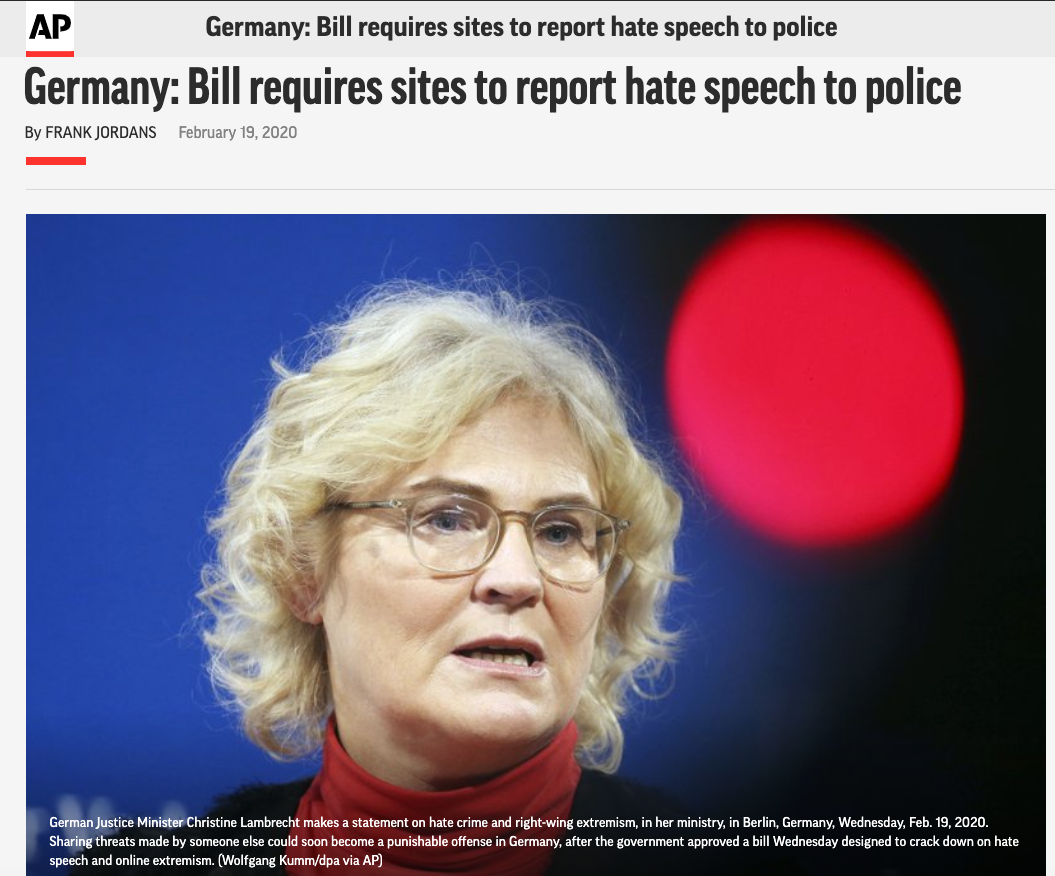

The German Cabinet approved a bill on February 19 that would require major social media platforms to report hate speech to the police.

The draft law would extend the NetzDG and link the “reporting requirement” in the draft law to the current regulations. This would require social media platforms to delete illegal material and flag content to the Office of the Federal Criminal Police (BKA). Offenses would extend to threats of murder, incitement of terrorist attacks, child pornography and any extremist propaganda.

Transparency reports disclosed by social media sites have given a strong indication of the reach that the draft law could affect. For example, following the first half of 2019, the draft law would have covered 35,000 videos from YouTube.

The bill must now be approved by the German parliament.

A second amendment (here in German, there’s no translation to English yet) was presented to the government on April 1st. This bill demands that the reporting channels must be easy to find and easy to use for everyone.

Germany’s Federal Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection, Christine Lambrecht, said:

“With the reform we are strengthening the rights of users of social networks. We make it clear: reporting channels must be easy for everyone to find and easy to use. Anyone who is threatened or insulted on the Internet must be able to report this to the social network simply and straightforwardly. Furthermore, we are simplifying the enforcement of information claims: Anyone who wants to defend themselves against threats or insults in court should be able to demand the necessary data much more easily than before. We are also improving protection against unauthorized deletions: In future, affected parties will be able to demand that the decision to delete their posts be reviewed and substantiated. This increases transparency and protects against unauthorized deletions.”

My Two Cents

I used to live in Germany, and still have friends in Eichstatt, Nuremberg, Cologne and Bremen. I wanted to interview them to add their opinions to the story, but when I asked them if we could talk about the NetzDG, none of my six friends there knew what it was. This is obviously a very small sample, and my friends do not work with media or communications – two are physicians, and the others work in universities in their academic fields (geography and economy). Still, having consulted many articles, opinions and scholarly papers, I assumed that the term or at least the concept would have become public knowledge. I understand that the law was contentious during its drafting and upon its implementation, having been left out of the media agenda on a second moment.

I concluded from my readings that the law did not keep the population from using hate speech on social media platforms, and that as of today, there are no drastic changes in the society’s behavior. Some may argue that the discussion led to nothing, but in my opinion, the law brought to the foreground a deep social issue that affects not only Germany, but the whole world. I believe that the country learned from the discussions that the law raised, and that someone at last stood up to companies like Facebook.