It’s complicated: the Brazilian relationship with WhatsApp

Street in Sao Paulo

* This story has not been adapted to cellphone screens yet *

SAO PAULO – JAN. 30, 2021 – Bernardo Araujo had just arrived home from work in Sao Paulo when he received a call from his sister. Their mother had just passed away in Rio de Janeiro. It was a Tuesday night in July 2019.

Araujo flew to Rio early Wednesday morning. While processing the loss with his family, he was also dealing with the Brazilian bureaucratic process relating to deaths. Hospital, funeral and cemetery documents had to be signed and sent out in a coordinated sequence, following strict Brazilian administrative rules.

Death in Brazil, a tropical country, gives no time for pause. The burial takes place 24 hours after the passing, if that long. In the Araujo family case, while the wake was taking place in the cemetery, a staff member realized that one of the original funerary documents was missing and the burial could not proceed. Araujo then sent a private WhatsApp message to the funeral home, and the document was immediately sent as a photo. The cemetery staff accepted the image instead of the original document and the burial was approved. Had Mr. Araujo gone through the same process a few years ago, the burial would have had to wait for the next day.

The Brazilian Zap Zap

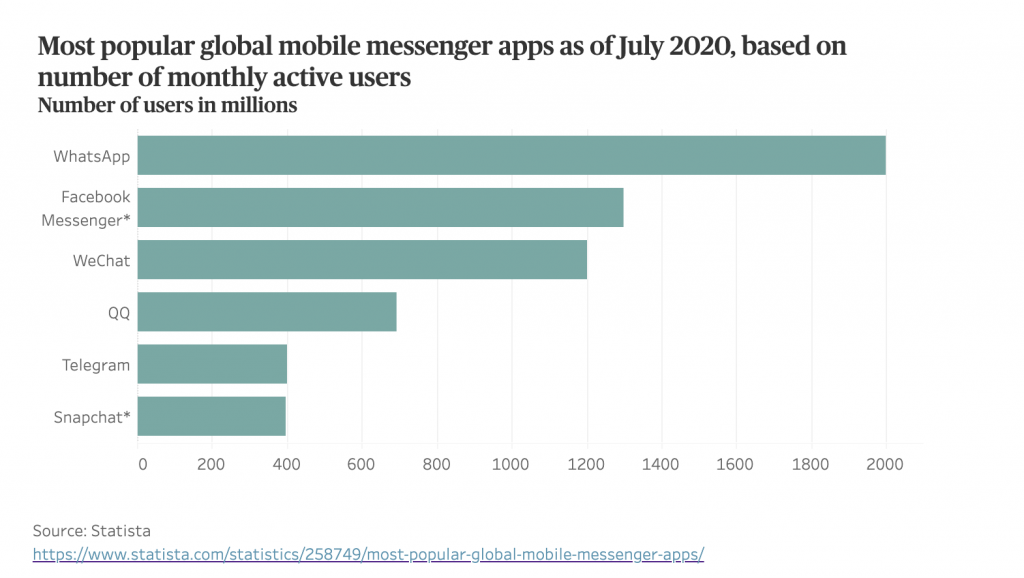

WhatsApp is not widely used in the U.S, however, it represents “the default” for messaging elsewhere in the world. It changed the way Brazilians communicate. Whether because of the possibility of communicating with different groups, calling a cab, ordering a pizza, scheduling a doctor visit, or being able to have a secure, private talk, people in Brazil love WhatsApp (nicknamed Zap Zap, or Zap, for short). It became a trusted, popular and ubiquitous tool that gained the trust of even the most bureaucratic systems.

“People buy cellphones today to have access to data more than any other reason,” says Araujo, who is a telecommunication system analyst in Sao Paulo. “There was a time when a TV or refrigerator was the Brazilian family’s most desired object. Today it is the cellphone. Whether you live in a favela and share one cellphone with a family of four or on in a beachside penthouse in Ipanema, everyone needs unlimited data plans and messenger apps. WhatsApp solves a lot of problems because it does not demand immediate attention like a text message. People feel free to respond at their convenience.”

Did the widespread use of unlimited data cellphone plans in Brazil gave WhatsApp a solid base for growth, or was it the other way around? It looks like this was a symbiotic and mutually empowering partnership.

Brazilians use the app to fit their gregarious nature. One of Araujo’s many WhatsApp groups, for example, consists of 8 childhood friends who share jokes, personal and professional problems, favors and old secrets. The group is a loyal and constant company that proves that nobody should ever feel alone – not even for one day. Brazilians don’t seem to know the concept of loneliness.

The Double-edged Sword

When former president Dilma Roussef was impeached in 2016, social media elevated political polarization to another level. The content circulated in WhatsApp was unique with its memes and political forces capitalized on the Brazilian uneducated masses access to the phone. Around that time Brazilians understood the potential that this new form of communication represented. WhatsApp was not to be underestimated.

Since the years following the impeachment, the app has been frequently seen as the main vector of the massive propaganda campaign that culminated in the election of Jair Bolsonaro. The Guardian analyzed a sample of 11,957 viral messages during the campaign period. It uncovered that approximately 42% of rightwing items contained information found to be false by factcheckers.

Measuring disinformation on WhatsApp can be tricky. Unlike Facebook and Twitter, WhatsApp is a private, encrypted chat tool, which means that a lot of its content is out of reach. It can be hard to figure out whether new changes, such as the forwarding limit, are really working.

Viktor Chagas, a researcher at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) in Rio de Janeiro, was curious about how fast political messages were spreading during the 2018 elections, so he joined numerous WhatsApp groups with the intent of collecting data. After months of watching the groups’ dynamics, he concluded that there was a solid and professionally organized pro-Bolsonaro network, with at least three main subgroups performing specific functions: creating content, mobilizing population and discussing strategy. In an interview given to Vice in 2018, Chagas explains that “the strategy created by Bolsonaro in 2016 was similar to that of Donald Trump’s campaign in 2016 [with its automatic distribution systems], but it was more innovative because of the nature of the app.”

It was not until October 2019, at the Festival Gabo in Colombia, that WhatsApp recognized its role in the Brazilian elections. Until then, the company had kept silence. Ben Supple, WhatsApp Global Head of Civic Engagement, admitted that the company knew about the large number of messages being sent out by certain businesses, in a reference to bots and automation in general.

In April 2020, WhatsApp announced a new restriction on message forwarding. It had already limited the number of individuals per group in 2019, but now it constrained the number of times a message could be shared at a time.

A study discussed by the MIT Technology Review suggested that the recent change is offering significant delays in the dissemination of information. Chagas maintains that the new limitations are part of a strategic move by Facebook to show some action toward the spreading of disinformation. In an interview over WhatsApp he says, “limiting the number of forwarded messages might have represented a small inconvenience for the daily user but did nothing to the vast and vascularized propaganda networks. We have an established political disinformation network with granular automatic distribution systems.”

When asked if WhatsApp had been good to Brazil, Araujo says “we can’t attribute everything that happened in this country to social media and messenger apps. WhatsApp allowed people to break their isolation bubbles during the pandemic. It was crucial for our mental health.”